POL 304: Using Data to Understand Politics and Society

Linear Regression

Olga Chyzh [www.olgachyzh.com]

Today's Agenda

Review of Section 4.3 of QSS Chapter 4

Regression and causality

Regression with multiple predictors (categorical IV)

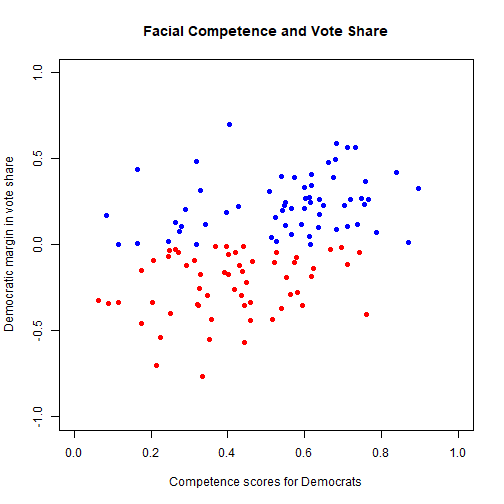

Which Person is the More Competent?

- 2004 Wisconsin Senate Race

Which Person is the More Competent?

2004 Wisconsin Senate Race

Russ Feingold (D) 55% vs. Tim Micheles (R) 44%

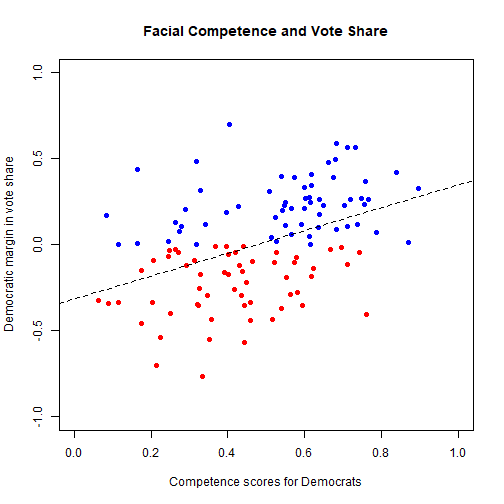

Facial Competence and Vote Share

Best Fit Line

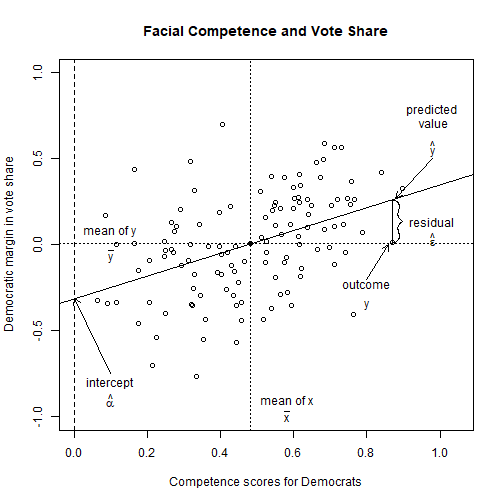

Linear Regression Model

- Model

Y=αintercept+βslopeX+ϵerror term

Y: dependent/outcome/response variable

X: independent/explanatory variable, predictor

(α,β): coefficients (parameters of the model)

ϵ: unobserved error/disturbance term (mean zero)

Interpretation:

α+βX: mean of Y given the value of X

- This is the line

β: increase in Y associated with one unit increase in X

For every 1-unit increase in X, there is a β change in Y

This works in reverse as well: For every 1-unit decrease in X, there is a −^β change in Y

α: the value of Y when X is zero

- Be careful! This number is not always meaningful

Facial Competence and Vote Share

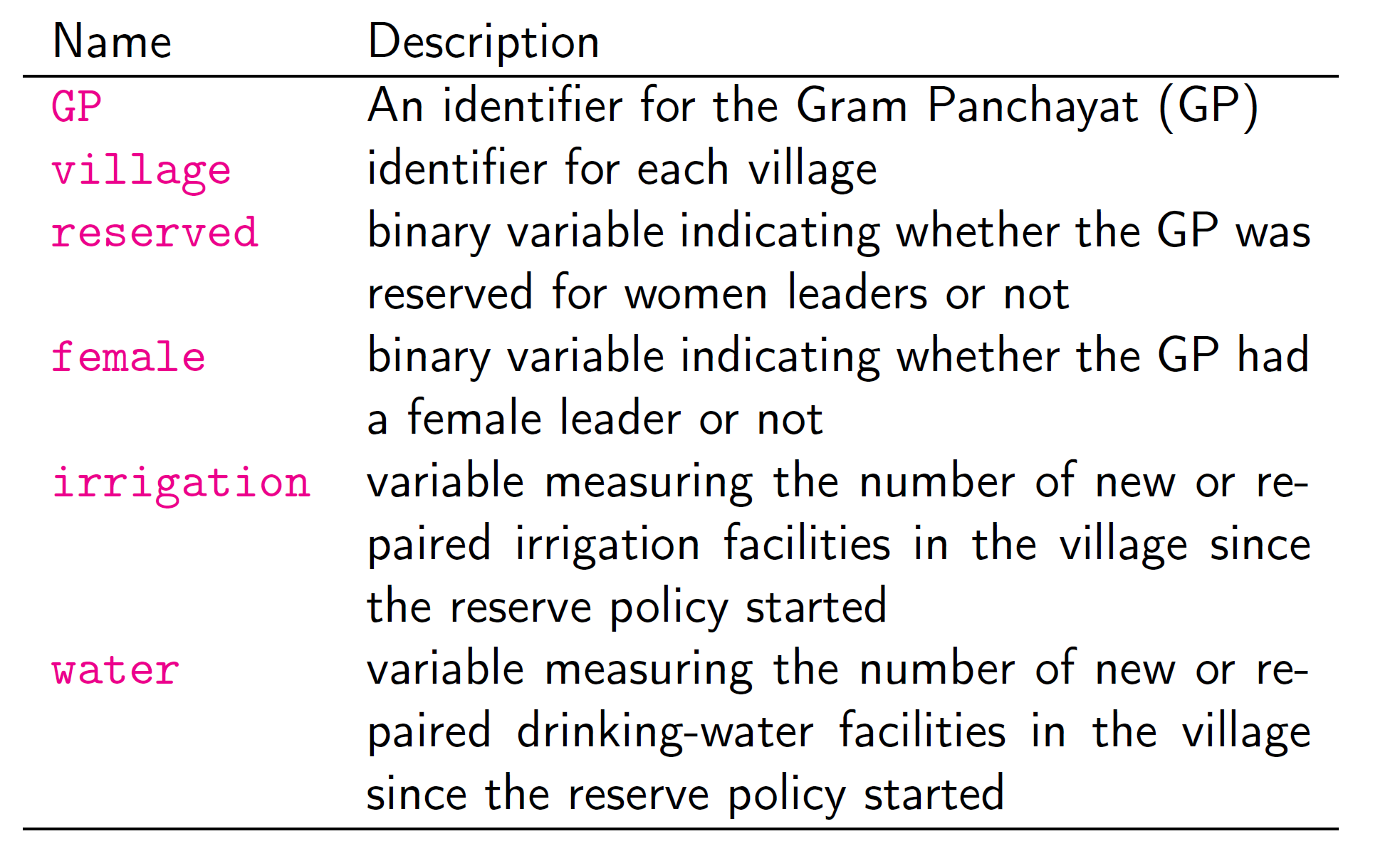

Women as Policy Makers

Do women promote different policies than men?

Observational studies: compare policies adopted by female politicians with those adopted by male politicians

Randomized natural experiment:

one third of village council heads reserved for women

assigned at the level of Gram Panchayat (GP) since mid-1990s

each GP has multiple villages

What does the effects of female politicians mean?

Hypothesis: female politicians represent the interests of female voters

Female voters complain about drinking water while male voters complain about irrigation

Does the reservation policy increase female politicians?

Proportions of women in reserved/non-reserved GP:

| Reserved | Not Reserved |

|---|---|

| 1 | 0.075 |

Does it change the policy outcomes?

## drinking-water facilitiesmean(women$water[women$reserved == 1]) - mean(women$water[women$reserved == 0])## [1] 9.252423## irrigation facilitiesmean(women$irrigation[women$reserved == 1]) - mean(women$irrigation[women$reserved == 0])## [1] -0.3693319Slope Coefficient = Difference-in-Means Estimator

- Randomization enables a causal interpretation of estimated regression coefficient ⇝ this is not always the case

mean(women$water[women$reserved == 1]) - mean(women$water[women$reserved == 0])## [1] 9.252423lm(water ~ reserved, data = women)## ## Call:## lm(formula = water ~ reserved, data = women)## ## Coefficients:## (Intercept) reserved ## 14.738 9.252Linear Regression with Multiple Predictors

The model:

Y=α+β1X1+β2X2+…+βpXp+ϵ Sum of squared residuals (SSR):

SSR=n∑i=1^ϵ2i = n∑i=1(Yi−^α−^β1Xi1−^β2Xi2−⋯−^βpXip)2

Multiple Regression

Most outcomes of interests Y are multi-causal;

Researchers are often interested in isolating the effect of the hypothesized theoretically relevant variable X;

Use multiple regression to statistically ''control for'' other causal variables Z.

Multiple Regression

- Move from a simple regression of: Yi=α+βXi+ϵi

- to a multiple regression of: Yi=α+β1Xi+β2Zi+ϵi, where Yi is the dependent variable, Xi and Zi are independent variables, and ϵi is the error term, for observation i, α is the constant, β1 and β2 are the coefficients associated with X and Z, respectively.

Multiple Regression

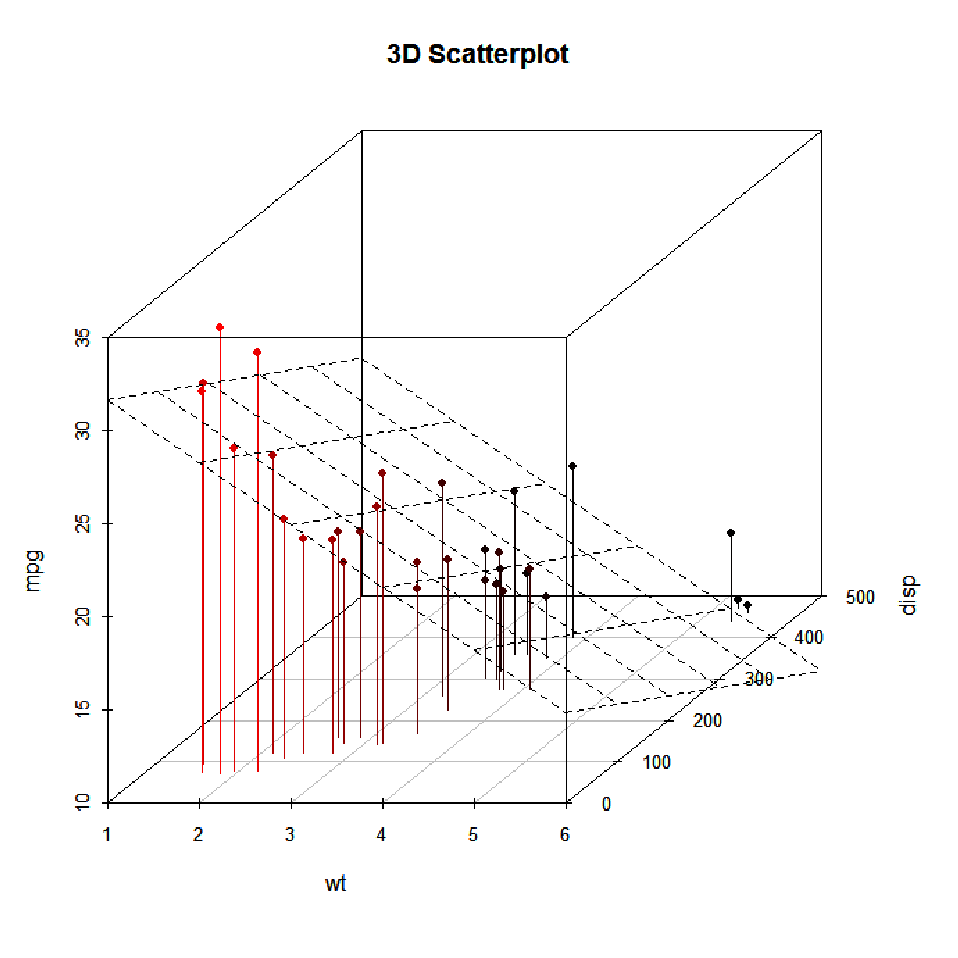

For simple regression, we thought of β as the steepness of the best fitting line that ran through a scatterplot;

For multiple regression, it is the same idea, but not it is multi-dimensional:

- Rather than two dimensions-- x and y axis--visible with a scatterplot, we are moving to three or more dimensions.

Multiple Regression

- Example of three dimensional space:

Multiple Regression

Same ''for every one-unit change'' interpretation, but now controlling for (holding constant) the effect of another independent variable;

β1 is the effect of X on Y, while holding the effect of Z constant;

β2 is the effect of Z on Y, while holding the effect of X constant;

Lab

The Social Pressure Experiment

Green, Gerber, and Larimer (2008)

Randomization of Treatments Enables Causal Interpretation

social <- read.csv("data/social.csv")social$messages<-as.factor(social$messages)levels(social$messages) # base level is `Civic'## [1] "Civic Duty" "Control" "Hawthorne" "Neighbors"fit <- lm(primary2008 ~ messages, data = social)round(coef(fit),3)## (Intercept) messagesControl messagesHawthorne messagesNeighbors ## 0.315 -0.018 0.008 0.063- The baseline category, the Intercept, is Civic Duty

Let's make Control the baseline category

- Create a binary indicator variable for each of the 4 categories

social$control<-as.numeric(social$messages=="Control")social$civic<-as.numeric(social$messages=="Civic Duty")social$hawthorne<-as.numeric(social$messages=="Hawthorne")social$neighbors<-as.numeric(social$messages=="Neighbors")fit1<-lm(primary2008 ~ civic+ hawthorne+ neighbors, data = social)round(coef(fit1),3)## (Intercept) civic hawthorne neighbors ## 0.297 0.018 0.026 0.081Fitted Values

- The predicted values give the average outcome under each condition

predict(fit, newdata = data.frame(messages = unique(social$messages)))## 1 2 3 4 ## 0.3145377 0.3223746 0.2966383 0.3779482tapply(social$primary2008, social$messages, mean)## Civic Duty Control Hawthorne Neighbors ## 0.3145377 0.2966383 0.3223746 0.3779482Your Turn

Create a new variable age that equals to 2008- the year of the respondent's birth.

Estimate the same model of the experimental treatment on turnout, but now also control for respondent's age.

Did the effect of each treatment change?

What is the effect of age on turnout?

What is the expected turnout for 18-year-olds? for 40-year-olds?